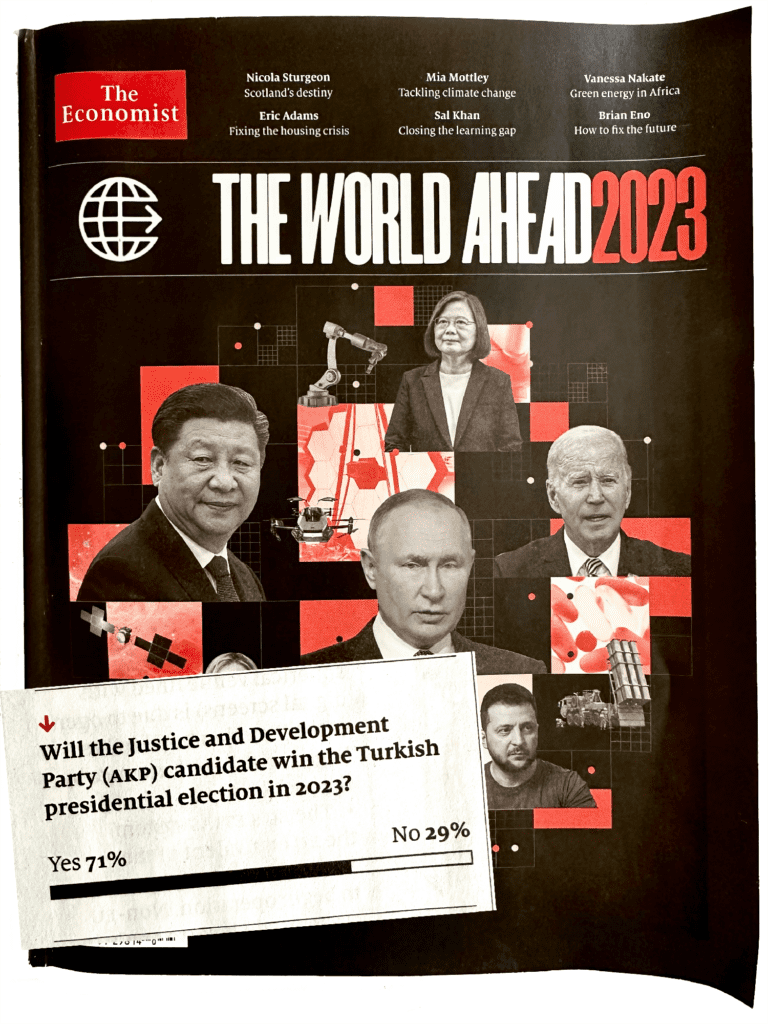

When The Economist’s “The World Ahead” issue was being prepared for publication in October 2022, Good Judgment’s professional Superforecasters were assigning a 71% probability to President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s victory in the 2023 Turkish presidential election. Since then, we witnessed Erdogan’s increasingly unorthodox fiscal policy that resulted in high inflation and a devastating earthquake that killed more than 50,000 people. These developments led many in the West to start betting on the candidate from Turkey’s united opposition, Kemal Kilicdaroglu. Superforecasters, however, stayed the course. With a one-day dip to 50-50 just ahead of the first round, they otherwise remained consistently at 60–70% for Erdogan throughout the seven months of this question period, and they are currently at 98%.

For Foreign Policy Expert and Superforecaster Dr. Balkan Devlen, this question was close to home. Born in Izmir, Turkey, Dr. Devlen felt many in the media were getting carried away by the narrative of an underdog win. In this interview, he discusses the key drivers behind his forecast, factors that Western commentators failed to take sufficiently into account, and his assessment of what lies in store for Turkey—and the region—after the election.

GJ: The Superforecasters started at 71% for Erdogan. They are now at 98%. How has your forecast evolved over this period? What were the key drivers?

BD: I was consistently around 80–85% throughout the question period. In that sense, my forecast didn’t evolve much, primarily because the key drivers of my forecast didn’t really change.

Number one is the makeup of the electorate in Turkey, which consistently suggests that about 40% of the voters support the more conservative nationalist coalition led by Erdogan. And that didn’t change much over the period, despite difficulties when it comes to economics or other issues.

Number two is the fact that Erdogan has been in power over 20 years, and during that period managed to install his own cadres across the state and bureaucracy, as well as to gain control over almost all of the media. This created an information environment in which the opposition had a hard time reaching voters who were not already anti-Erdogan.

Lastly, Erdogan does not have the luxury of losing. The extreme polarization within Turkish society and Erdogan’s increasing authoritarianism, especially in the last 10–12 years, means that retiring after the election is just not an option for him, and his family and cronies have also been implicated throughout his rule in corruption, oppression of free speech and freedom of media, etc. Taking those three drivers together, I did not see the wherewithal that the opposition can come together and push out a win.

GJ: Several polls and many commentators in the West were predicting that the opposition would win. Did you find their arguments convincing?

BD: I did not find the polling or the Western commentary particularly convincing, primarily because they tend to base their arguments as if the elections were taking place without the context that I’ve just discussed. I also think that some were engaging in motivated reasoning and wishful thinking. One argument is that the impact of the earthquake in Turkey could have shifted the balance, but that again is a misunderstanding of the fundamental dynamics in the region.

GJ: What would have made you change your forecast?

BD: Perhaps two things. One, if there had been another candidate, either Istanbul Mayor Ekrem Imamoglu or Ankara Mayor Mansur Yavas, the opposition would have had a much better chance.

Two, if I were to see any high-level defections from the AKP or the close circle of Erdogan prior to the election, that would have suggested that, at least, there is a fracture within the ruling elite, that they were considering their post-election fates, and therefore they were breaking rank and jumping ship. We didn’t see any of that, so I didn’t see any reason to change my forecast.

GJ: Superforecasters as a group are now at 98% probability for Erdogan’s victory. Is there a chance they’re wrong?

BD: Of course, there is a chance that the Superforecasters could be wrong, and I am at 98% myself. There are always black swan events, despite the fact that there are only a few days left before the second round. But I don’t see any particular dynamic today that would suggest that the fundamentals prior to the first round were altered in any meaningful way.

Incidentally, I was expecting that this would go to the second round, partly because of the third-party candidate, Sinan Ogan, who now declared his support for Erdogan. That base will probably break 2-1, at least, for Erdogan. But the implication is that if Ogan weren’t in the running, Erdogan probably would have won in the first round.

GJ: What’s in store for Turkey now and for the region?

BD: Well, that’s a big question and I don’t think that’s enough space to go into a detailed examination. But I can tell you that the region and Turkey will probably need to accept the fact that Erdogan will be in power as long as he’s alive. And actors in Europe, in the Middle East, in the Caucasus, and elsewhere would need to adjust to that particular fact.

For Turkey, the results would not lead to a more democratic system. There are those in the parliament now, as part of Erdogan’s coalition, who are hardcore Islamists, and who are calling for much more Islamist policies, for example.

The election results will also lead to recriminations among the opposition coalition, as the only thing that really unites them is their opposition to Erdogan. Therefore, one can expect turmoil within the opposition parties in the post-election era.

Erdogan will probably consolidate his power. That might provide some stability in terms of regional policies now that the need to play for domestic audiences has decreased. Therefore, we are likely to see a more predictable foreign policy attitude from Turkey. I do not necessarily see, though, much change in the direction in which Erdogan wants to take the country, both domestically and internationally.

I don’t see Sweden’s membership being approved by the Turkish parliament before the end of summer as it’s just not a priority, although timing is very hard to predict in these cases.

But like I said, a proper answer to this question requires much more detail and a much longer exposition than can be provided in a short interview. One thing is quite clear, though, and that is Erdogan will be in power for the foreseeable future.

Schedule a consultation to learn how our FutureFirst monitoring tool, custom Superforecasts, and training services can help your organization make better decisions.