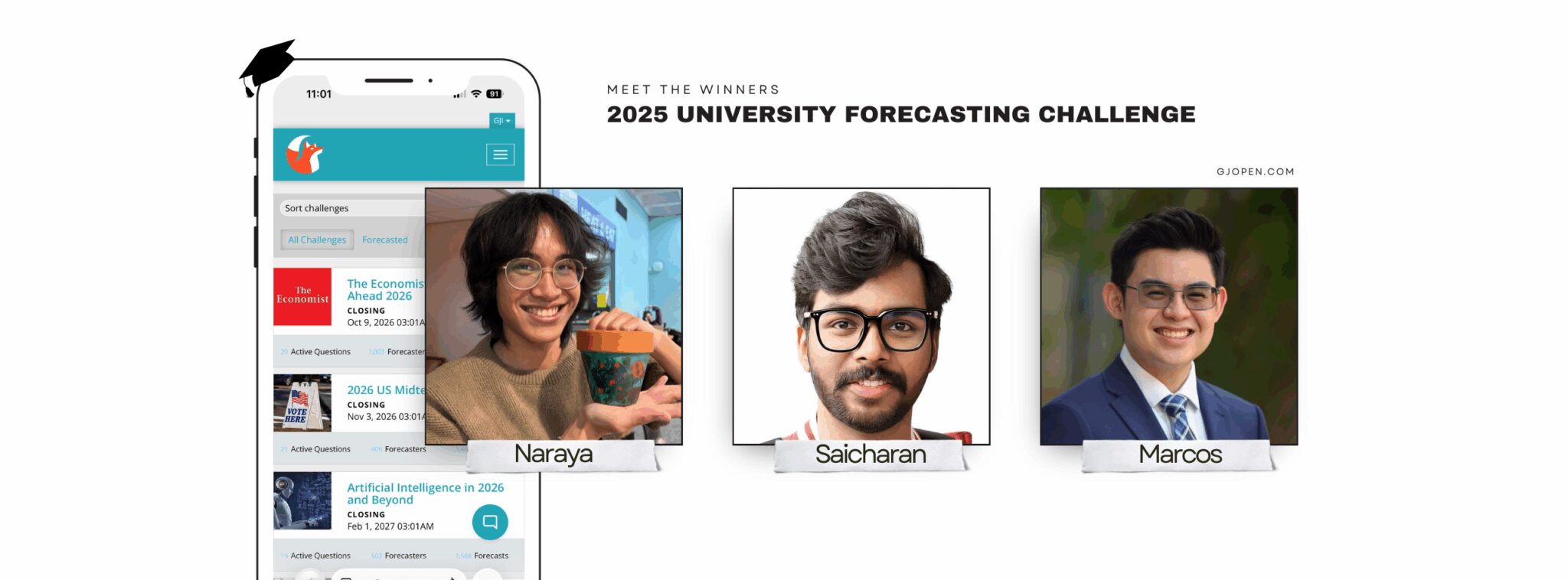

Meet the Winners of the 2025 University Forecasting Challenge

From August to December 2025, students from universities around the world tested their forecasting abilities on GJ Open. The 2025 University Forecasting Challenge asked participants to make predictions on topics ranging from economic indicators and political developments to literary prizes, updating their forecasts as new information emerged.

We spoke with the top three finishers about their strategies, their struggles, and how the discipline of forecasting has shaped the way they think.

The Winners

Naraya Papilaya

University of Edinburgh | BSc Biological Sciences (Honours in Genetics)

An Indonesian third-year undergraduate student and trustee at the Edinburgh University Students’ Association. They enjoy researching macrosystems and are involved in student politics and policy development.

Saicharan Ritwik Chinni

BITS Pilani (Mathematics & Electronics) | IIT Madras (Data Science)

A recent graduate with a master’s degree in mathematics who completed thesis work at the Yale School of Public Health and is currently working on an independent startup idea.

Marcos Ortega

University of Florida | Honors Finance

A portfolio manager at Caimanes, a student-managed equity hedge fund, with a broad passion for markets and research. In his free time, he enjoys fire juggling, reading, and weightlifting.

The Interview

GJO: What first drew you to forecasting, and how did you hear about the University Forecasting Challenge?

Naraya: I picked up Phil Tetlock’s Superforecasting during lockdown and found its concepts fascinating. It was a little comforting amidst the global chaos. In 2025, forecasting became a way to test the accuracy of my models about the world. I was already an active forecaster on The Economist’s 2025 challenge; the University Forecasting Challenge was my way to test whether six months of deliberate practice had meaningfully improved my calibration.

Saicharan: What drew me to forecasting was the opportunity to think rigorously about uncertainty and real-world outcomes. I heard about the challenge through an email from GJO and decided to participate as a way to benchmark my thinking in a competitive setting.

Marcos: I was introduced to forecasting through Metaculus because of its collaboration with Bridgewater Associates in Spring 2025. I found that the forecasting process was akin to my debate research process, which I competed in for seven years. The variety of topics, the synthesis of different perspectives, and the consistent news updates felt somewhat nostalgic. After I read Superforecasting, I wanted to see if the Good Judgment Project was still around, and I ended up stumbling upon the University Forecasting Challenge.

GJO: Walk us through your approach. How did you tackle a question from start to finish?

Naraya: I mainly rely on the CHAMPS-KNOW framework, systems thinking, and diligence. I start by calculating plausible base rates; only then do I analyze the crowd’s prediction. But I mostly try to quantify the extent of uncertainties inherent within a question and identify key future developments to expect. Politics seems to be the most subject to change. These questions linger on my mind day-to-day, which generates random insights, so I update quite often.

Saicharan: My core strategy was to stay consistently updated with current affairs and relevant news. I typically start by understanding the resolution criteria, then try to connect the dots using theory-driven reasoning and available data when possible. Over the course of the challenge, my approach became more structured. I learned to rely less on intuition alone and more on explicit assumptions and disciplined updates as new information emerged.

Marcos: Initially, I establish a foundation by looking at historical precedent, crowd forecasts, large language model outputs, and prediction market probabilities. I preferred questions with time series data because of my familiarity with forecasting time series and the ease of establishing base rates. Once I had an established foundation, I would research the context affecting the question to form an inside view, then nudge my judgment upward or downward to finalize my forecast.

Later in the tournament, I started incorporating the “Activity” feed in my analysis because I could see individual forecasts. Oftentimes, forecasts would be extremely skewed toward one outcome, so I would attempt to form a believability-weighted crowd forecast. I trusted forecasters with less extreme views since it’s rare for forecasts to be fully certain.

GJO: Which question did you find most difficult, and how did you work through the uncertainty?

Naraya: The Manheim Used Vehicle Value Index question was the most difficult. I’m decent at macroeconomic forecasts, but the auto industry is completely foreign territory for me. I initially put a wide spread of predictions, but I got overconfident and put all my eggs on a slight increase in the index. In the end, I overestimated the impact of tariffs and underestimated the strength of the US economy and consumer behavior.

Saicharan: I also found the Manheim question particularly challenging. I analyzed the historical values for the year and used measures of dispersion, such as standard deviations, to assess how tightly clustered the data were. Based on this analysis, I assigned higher probability mass to a relatively narrow range of outcomes. This approach aligned well with realized outcomes for most of the competition, but then the mid-October value dropped sharply into a bucket I had initially assigned only the second-highest probability. It was a useful reminder that even when data appear stable, deviations can still occur.

Marcos: I found the question about the 2025 Booker Prize the most difficult due to the wide uncertainty in deriving the underlying qualifications of the literature that typically wins. I decided to maintain relatively close to baseline rates for most of my predictions, approximately 16.7% probability since there were six options. I felt the crowd was far too confident, deviating very far from the baseline rates for certain books. This difference in approach led to my best performance on the question: it contributed over half of my overall relative Brier score.

GJO: How do you decide when to update a forecast? What signals tell you it’s time to revise your thinking?

Naraya: I’ve found it useful to prepare a list of outcomes you’d expect over the next weeks or months. On a good forecast, outcomes that fit my “model” should naturally develop with time. I revise forecasts when new information meaningfully contradicts my expectations. This is why visually mapping out the interplaying systems can be so helpful.

Saicharan: It varies by question type. For market-related questions, such as those involving the S&P 500, I rely more on data-driven methods. I download historical data from FRED and run Monte Carlo simulations using an app I built, typically revisiting and updating these forecasts weekly. For macroeconomic or policy-focused questions, qualitative signals play a larger role: news coverage, Reuters reports, labor market data, and statements from the Fed Chair. For electoral questions, I use opinion polls to inform my baseline expectations and adjust as new polling data is released or as trends become clearer. Overall, my update strategy is driven by whether new information meaningfully changes the structure of uncertainty.

Marcos: For most of my forecasts, I aim to update them weekly because there’s typically new evidence that affects the likely resolution. I also set notifications when crowd forecast probabilities change more than a few percent. That indicates there’s new evidence to analyze. I tend to pay more attention to forecasts where I’m noticeably deviant from the crowd, because the crowd tends to be quite accurate overall.

GJO: How do you see forecasting skills applying to your studies or future career?

Naraya: Forecasting has immensely developed my ability to evaluate useful information versus noise. I’ve applied these skills in assessments, but they’ve been most useful in my trusteeship and strategic work. I especially enjoy integrating forecasting principles into strategy, and I’m keen to pursue future work and volunteering opportunities that value these skills.

Saicharan: Forecasting has helped me appreciate the value of being a generalist. The habit of thinking through diverse events on a daily basis has improved how I approach learning and problem-solving more broadly. It has also reinforced the importance of probabilistic thinking and updating beliefs in light of evidence. These are skills that are directly applicable to both academic work and analytical roles.

Marcos: I’m interested in a career in public markets, so it’s crucial to learn to make educated predictions about the future of markets and how a particular asset class or individual asset will perform. Forecasting has forced me to reflect whenever my forecasts diverge from the median, helping me calibrate my confidence and question whether I had uncovered a true edge or had overlooked something others had seen. It’s been an excellent way to cross-train this skill set, and I believe it has notable carryover effects on my approach to research at Caimanes.

GJO: What’s one mistake you caught, or one assumption you wish you had tested sooner?

Naraya: I initially assumed that Trump’s polling averages would be resilient, considering how little his tariff announcement changed things. Although this proved incorrect by mid-November, I revised my thinking and predicted an inherent shift in consciousness within independents and Gen Z toward Trump over the following months. This mistake taught me to better integrate uncertainties within my forecast, which proved very useful in other questions.

Saicharan: While forecasting the US president’s net approval rating, my initial forecast in August assumed that changes would be relatively gradual, so I distributed the probability mass broadly across the negative range. As new polling data arrived, I updated almost weekly, tracking short-term movements through rolling averages. But as the months progressed, approval ratings shifted more sharply following specific political developments. In hindsight, I focused too much on extrapolating recent trends and not enough on anticipating how major actions or events could structurally change public sentiment. Next time, I would place greater emphasis on identifying potential inflection points driven by policy decisions or political shocks.

Marcos: For the average nonfarm private payrolls, I overweighted the relevance of the 104,000 jobs added in July. Consequently, my initial forecast was centered between 40,000 and 80,000. I later realized that macroeconomic headwinds were causing a secular downward trend that would not cede within the performance period. Because roughly 13% of the question’s duration had already elapsed before I adjusted, this negatively impacted my Brier score. In the future, I will analyze the broader context more deeply and avoid overweighting individual data points.

Join the Next Challenge

GJ Open hosts forecasting challenges throughout the year. They’re free, open to everyone, and designed to sharpen exactly the kind of thinking these winners demonstrated. Whether you’re a student testing your calibration or a professional honing your analytical edge, there’s a place for you.

Ready to try? Visit gjopen.com to start forecasting today.

The 2025 UFC winners will each receive a seat in Good Judgment’s Superforecasting workshop, a two-day intensive that teaches the techniques used by some of the world’s most accurate forecasters.

Congratulations to Naraya, Saicharan, and Marcos. We look forward to seeing how you apply these skills in the years ahead.