Super Quiet: Kahneman’s Noise and the Superforecasters

Much is written about the detrimental role of bias in human judgment. Its companion, noise, on the other hand, often goes undetected or underestimated. Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment, the new book by Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman and his co-authors, Olivier Sibony and Cass R. Sunstein, exposes how noise—variability in judgments that should be identical—wreaks havoc in many fields, from law to medicine to economic forecasting.

Much is written about the detrimental role of bias in human judgment. Its companion, noise, on the other hand, often goes undetected or underestimated. Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment, the new book by Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman and his co-authors, Olivier Sibony and Cass R. Sunstein, exposes how noise—variability in judgments that should be identical—wreaks havoc in many fields, from law to medicine to economic forecasting.

Noise offers research-based insights into better decision-making and suggests remedies to reduce the titular source of error.

No book on making better judgments, of course, particularly better judgments in forecasting, would be complete without the mention of Superforecasters, and certainly not one co-authored by such a luminary of human judgment as Kahneman.

Superforecasters (discussed in detail in chapters 18 and 21 of the book) are a select group who “reliably out-predict their less-than-super peers” because they are able to consistently overcome both bias and noise. One could say, the Superforecasters are not only actively open-minded—they are also super quiet in their forecasts.

“What makes the Superforecasters so good?” the authors ask. For one, they are “unusually intelligent” and “unusually good with numbers.” But that’s not it.

“Their real advantage,” according to Kahneman, Sibony, and Sunstein, “is not their talent at math; it is their ease in thinking analytically and probabilistically.”

Noise identifies other qualities that set the Superforecasters apart from regular forecasters:

-

- Willingness and ability to structure and disaggregate problems;

- Taking the outside view;

- Systematically looking for base rates.

In short, it’s not just their natural intelligence. It’s how they use it.

Not everyone is a good forecaster, of course, and while crowds are usually better than individuals, not every crowd is equally wise.

“It is obvious that in any task that requires judgment, some people will perform better than others will. Even a wisdom-of-crowds aggregate of judgments is likely to be better if the crowd is composed of more able people,” the authors state.

Good Judgment’s Superforecasters are unique, with an unbeaten track record, among a myriad of individual forecasters and forecasting firms. Kahneman, Sibony, and Sunstein are not surprised:

“Judgments are both less noisy and less biased when those who make them are well trained, are more intelligent, and have the right cognitive style.”

Good Judgment’s Training Reduces Noise

“Well trained” is a key word here. When the Superforecasters were discovered in “some of the most innovative work on the quality of forecasting”—the Good Judgment Project (GJP, 2011-2016)—they were the top 2% among thousands of volunteers. That doesn’t mean, however, that the rest of the world is doomed to drown in noisy decision-making. It is not an either-you-have-it-or-you-don’t skill.

“Well trained” is a key word here. When the Superforecasters were discovered in “some of the most innovative work on the quality of forecasting”—the Good Judgment Project (GJP, 2011-2016)—they were the top 2% among thousands of volunteers. That doesn’t mean, however, that the rest of the world is doomed to drown in noisy decision-making. It is not an either-you-have-it-or-you-don’t skill.

According to Kahneman, Sibony, and Sunstein, “people can be trained to be superforecasters or at least to perform more like them.”

Good Judgment Inc’s online training and workshops do just that. Based on the concepts taught in the GJP training, these workshops are designed to reduce psychological biases—which, in turn, results in less noise.

Kahneman and colleagues explain how this works, citing the BIN (bias, information, and noise) model for forecasting developed by Ville Satopää, Marat Salikhov, and Good Judgment’s co-founders Phil Tetlock and Barb Mellers:

“When they affect different individuals on different judgments in different ways, psychological biases produce noise. … As a result, training forecasters to fight their psychological biases works—by reducing noise.”

Good Judgment’s training also focuses on teaming, another effective method scientifically demonstrated to reduce noise.

According to Kahneman, Sibony, and Sunstein, both private and public organizations—and the society at large—stand to gain much from reducing noise. “Should they do so, organizations could reduce widespread unfairness—and reduce costs in many areas,” the authors write. And the Superforecasters are an example for decision-makers to emulate in these efforts.

Learn Superforecasting from the pros at our Superforecasting Workshops

See upcoming workshops here

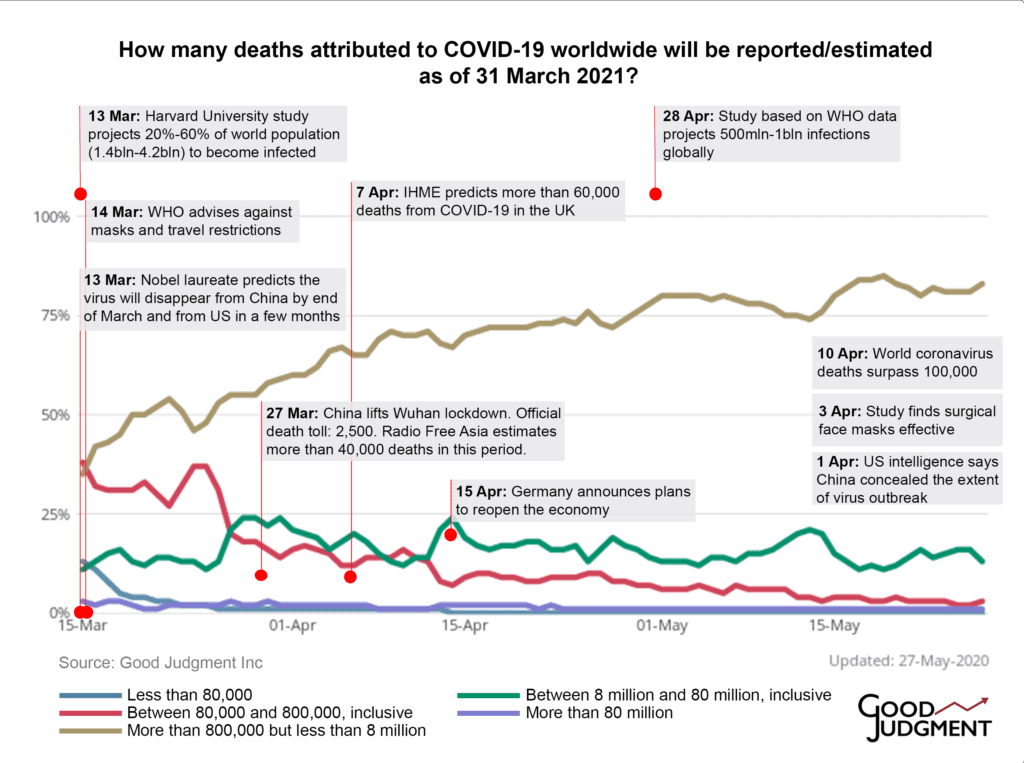

Think back to a year ago, when the airwaves were filled with experts and politicians confidently asserting that COVID-19 would swiftly pass. The US president claimed in February 2020 that the coronavirus was under control in the US and would disappear “like a miracle.” It took another month for the administration to acknowledge that the unfolding pandemic was

Think back to a year ago, when the airwaves were filled with experts and politicians confidently asserting that COVID-19 would swiftly pass. The US president claimed in February 2020 that the coronavirus was under control in the US and would disappear “like a miracle.” It took another month for the administration to acknowledge that the unfolding pandemic was  Hedgehogs tend to be more confident—and more likely to get media attention—but, as research has found in multiple experiments, they also tend to be worse forecasters. Foxes, in contrast, tend to think in terms of “however” and “on the other hand,” switch mental gears, and talk about probabilities rather than certainties.

Hedgehogs tend to be more confident—and more likely to get media attention—but, as research has found in multiple experiments, they also tend to be worse forecasters. Foxes, in contrast, tend to think in terms of “however” and “on the other hand,” switch mental gears, and talk about probabilities rather than certainties.