How Much Does Control of the Senate Matter?

Although seats occasionally change parties between elections, the Georgia runoffs are likely to determine partisan control of the Senate for the next two years. To get a sense of how much these elections matter, we posed four “conditional” questions on economic policy to the Superforecasters.

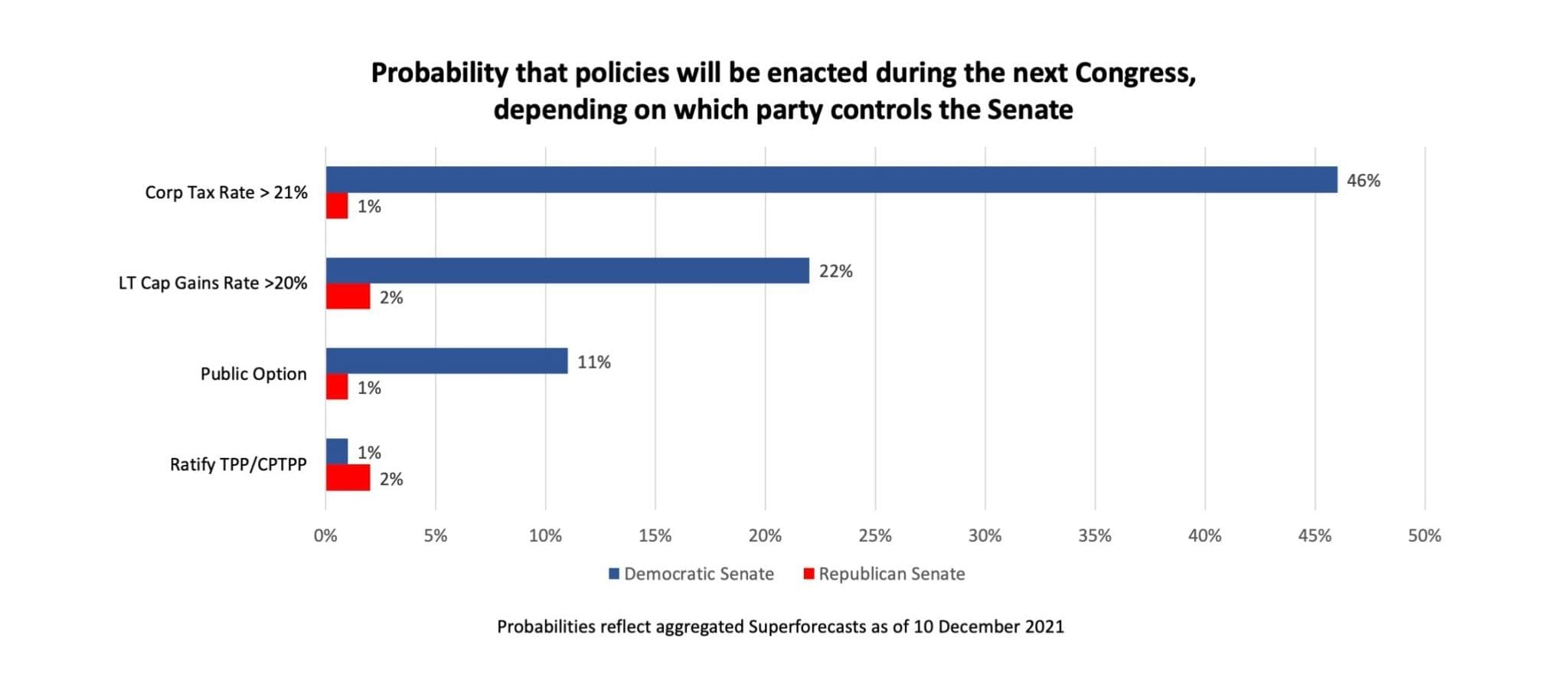

Bottom line up front: The Superforecasters see control of the Senate as having a large impact on the economic policies that the new administration will adopt, especially with respect to the top brackets for the long-term capital gains and corporate income taxes.

We’ll get to the detailed results shortly, after presenting some background on conditional questions.

How conditional questions work

Conditional questions present alternative scenarios. In this case, the two scenarios are:

-

- the Republicans retain control of the Senate (which will occur if the Republicans win at least one of the two Georgia seats), and

- the Democrats regain control of the Senate (which will only occur if the Democrats win both Georgia seats).

Forecasters estimate the probability that a given outcome will occur under each of the possible scenarios. For example, we posed the question “Before 1 January 2023, will legislation creating a ‘public option’ health insurance plan administered by the federal government become law?” and asked the Superforecasters to provide two different estimates of the likelihood that this outcome would occur: one if the Republicans control the Senate and the other if the Democrats regain control of the Senate.

Important to know: The probability estimates for the two scenarios do not have to add to 100%. In effect, each scenario is a stand-alone forecasting question, and the probabilities for each scenario can range from 0 to 100%.

If the Senate passes legislation relating to any of the policies, we will only score the branch of the conditional question that reflects which party was in power at that time. We will “void” (cancel) the other branch because that scenario would no longer apply.

Our questions

In addition to the public-option question, we asked Superforecasters about three other economic policies:

-

- Before 1 January 2023, will legislation raising the top marginal tax rate for long-term capital gains in the U.S. to higher than 20% become law?

- Before 1 January 2023, will legislation raising the top corporate tax rate in the U.S. to higher than 21% become law?, and

- Before 1 January 2023, will the United States ratify the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade agreement and/or the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP)?

In each case, the Superforecasters are providing separate probability estimates for the Republican- and Democrat-controlled Senate scenarios.

Forecasts as of 10 December 2020

The Superforecasters see a Democrat-controlled Senate as crucial to the success of the two tax policies and the public option. Even under those “best of circumstances,” as of December 10th, Superforecasters rated all three policies as having lower odds than a coin toss. Raising the top corporate tax rate above 21% is estimated to be the most likely of these policies to be enacted, but the Superforecasters assign only a 46% probability to that outcome under a Democrat-controlled Senate.

In contrast, the Superforecasters see little chance that the US will join either the TPP or the CPTPP before 2023, regardless of who controls the Senate. If anything, they see a Republican-controlled Senate as slightly more likely to bring this outcome to pass.

Put another way, the Superforecasters currently do not expect the Biden administration to get signature economic policy initiatives through the next Congress unless the Democrats win both Georgia runoff elections. Increases to the top corporate tax rate is 46 times more likely if the Democrats control the Senate; increases to the top long-term capital gains tax rate and enactment of a public option for health care are each 11 times more likely if the Democrats win the Georgia runoffs. The stakes are genuinely high. One Superforecaster® stated,

Put another way, the Superforecasters currently do not expect the Biden administration to get signature economic policy initiatives through the next Congress unless the Democrats win both Georgia runoff elections. Increases to the top corporate tax rate is 46 times more likely if the Democrats control the Senate; increases to the top long-term capital gains tax rate and enactment of a public option for health care are each 11 times more likely if the Democrats win the Georgia runoffs. The stakes are genuinely high. One Superforecaster® stated,

If someone from two years in the future came back to Dec. 2020 and told me these [tax] hikes didn’t happen, my first thought would be that Biden must be a failed president.

Get early insight into major geopolitical, economic, technological, and public health questions that impact the future with our FutureFirst™ dashboard. If there are other policy forecasts you’d like to see, please contact us to explore ways in which we can make that information available.

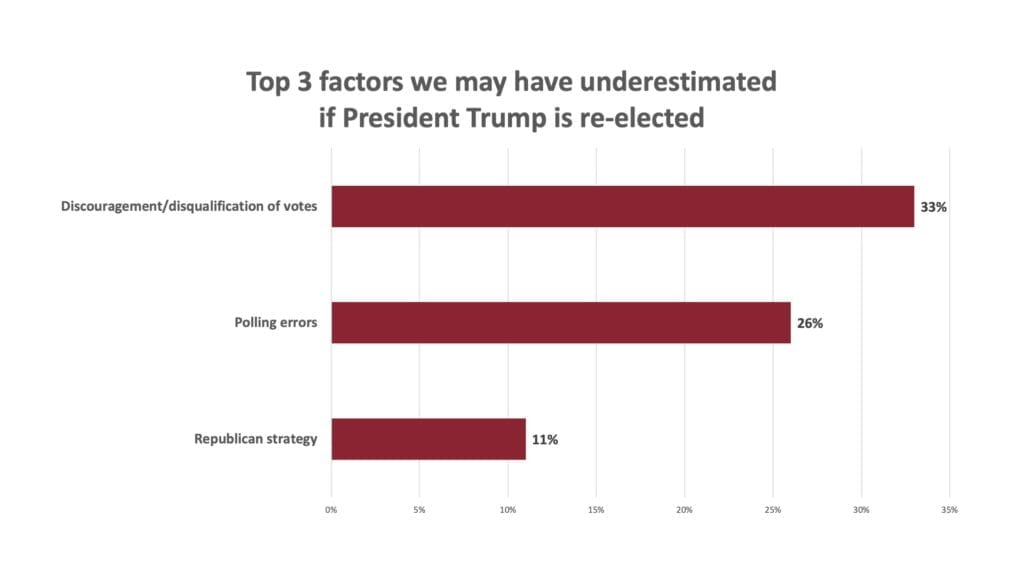

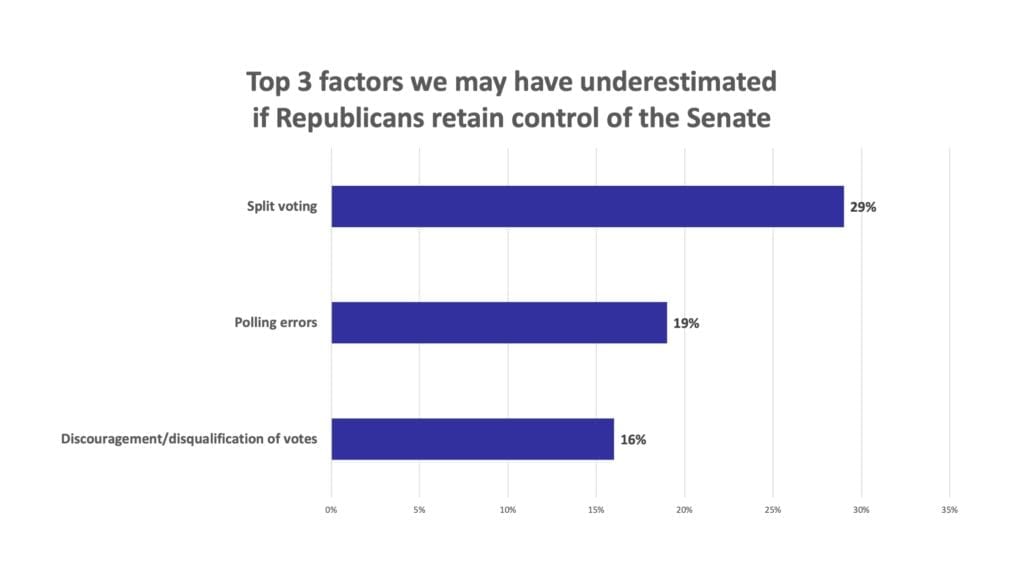

Over the week before the election, Good Judgment’s professional Superforecasters engaged in an extensive “pre-mortem” or “what-if” exercise regarding our forecasts for a Blue-Wave election. We asked the Superforecasters to imagine that they could time-travel to a future in which the 2020 election results are final, with the Republicans retaining both the White House and control of the Senate. Then, we asked them to “explain” why the outcomes differed from the most likely outcomes in their pre-election probabilistic forecasts. Thinking through these scenarios now, before the actual outcomes are known, helps to avoid hindsight bias (the tendency to view what actually happened as being more inevitable than it was).

Over the week before the election, Good Judgment’s professional Superforecasters engaged in an extensive “pre-mortem” or “what-if” exercise regarding our forecasts for a Blue-Wave election. We asked the Superforecasters to imagine that they could time-travel to a future in which the 2020 election results are final, with the Republicans retaining both the White House and control of the Senate. Then, we asked them to “explain” why the outcomes differed from the most likely outcomes in their pre-election probabilistic forecasts. Thinking through these scenarios now, before the actual outcomes are known, helps to avoid hindsight bias (the tendency to view what actually happened as being more inevitable than it was).