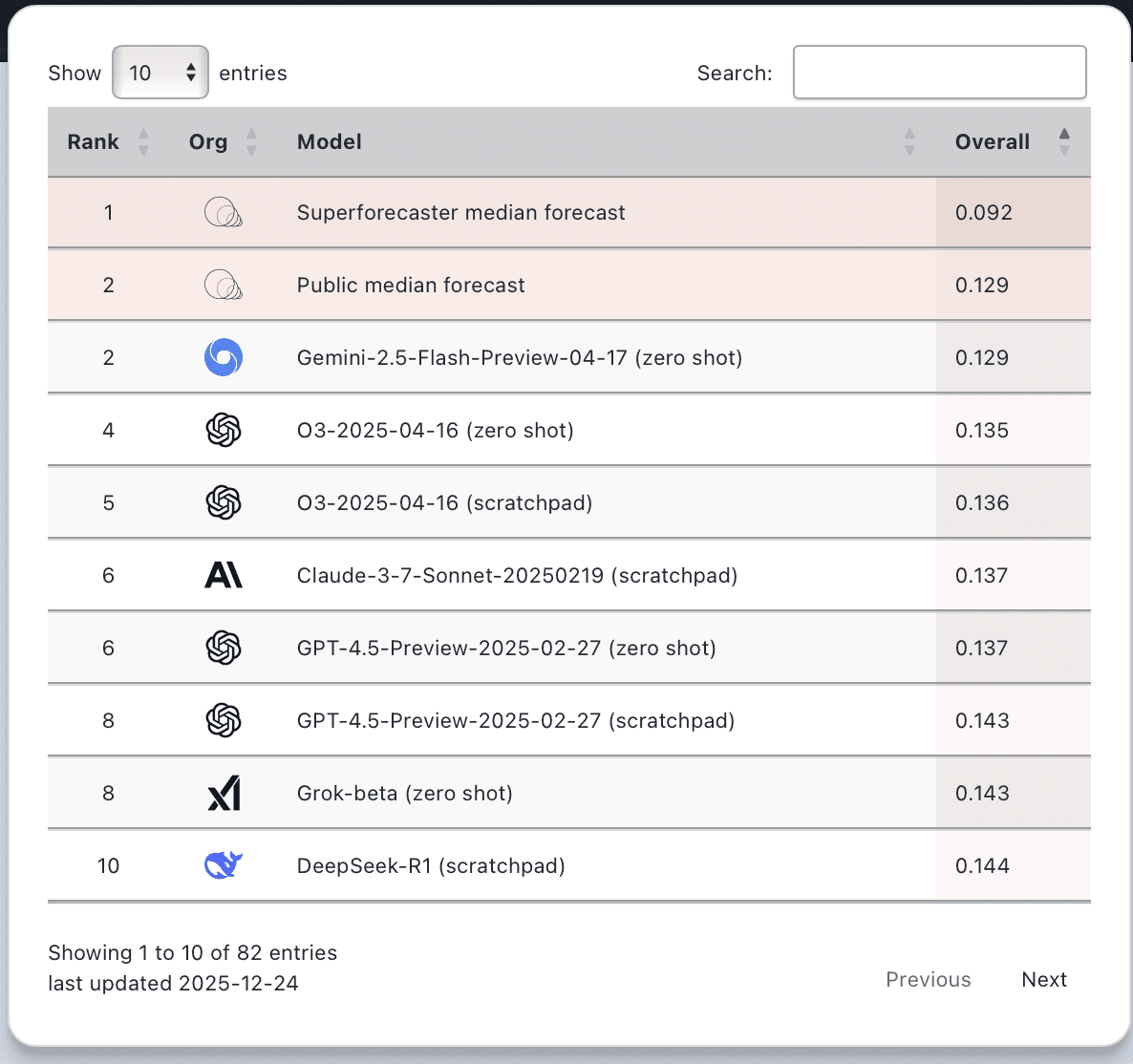

Testing Polymarket’s “Most Accurate” Claim

In the case of central bank forecasts, the claim does not hold up when compared to our panel of professional Superforecasters, writes Chris Karvetski, PhD, GJ Senior Data and Decision Scientist.

In a recent 60 Minutes segment, Polymarket CEO Shayne Coplan described his platform in sweeping terms: “It’s the most accurate thing we have as mankind right now. Until someone else creates sort of a super crystal ball.”

It’s a memorable line and an ambitious claim that, at least in the case of central bank forecasts, does not hold up when compared to our panel of professional Superforecasters.

Superforecasting emerged from more than a decade of empirical research, systematic evaluation, and the cultivation of best practices. Polymarket emerged from a very different ecosystem of venture capital, market design, and financial incentives. But origins, pedigrees, and resources ultimately do not decide accuracy. Head-to-head testing on matched forecasting questions does. Central bank rate decisions provide an ideal setting for such an evaluation, which is why we compared Polymarket and Superforecaster forecasts across the full set of 25 recent monetary policy meetings of the Federal Reserve, European Central Bank, Bank of England, and Bank of Japan for which forecasts from both platforms were available.[1]

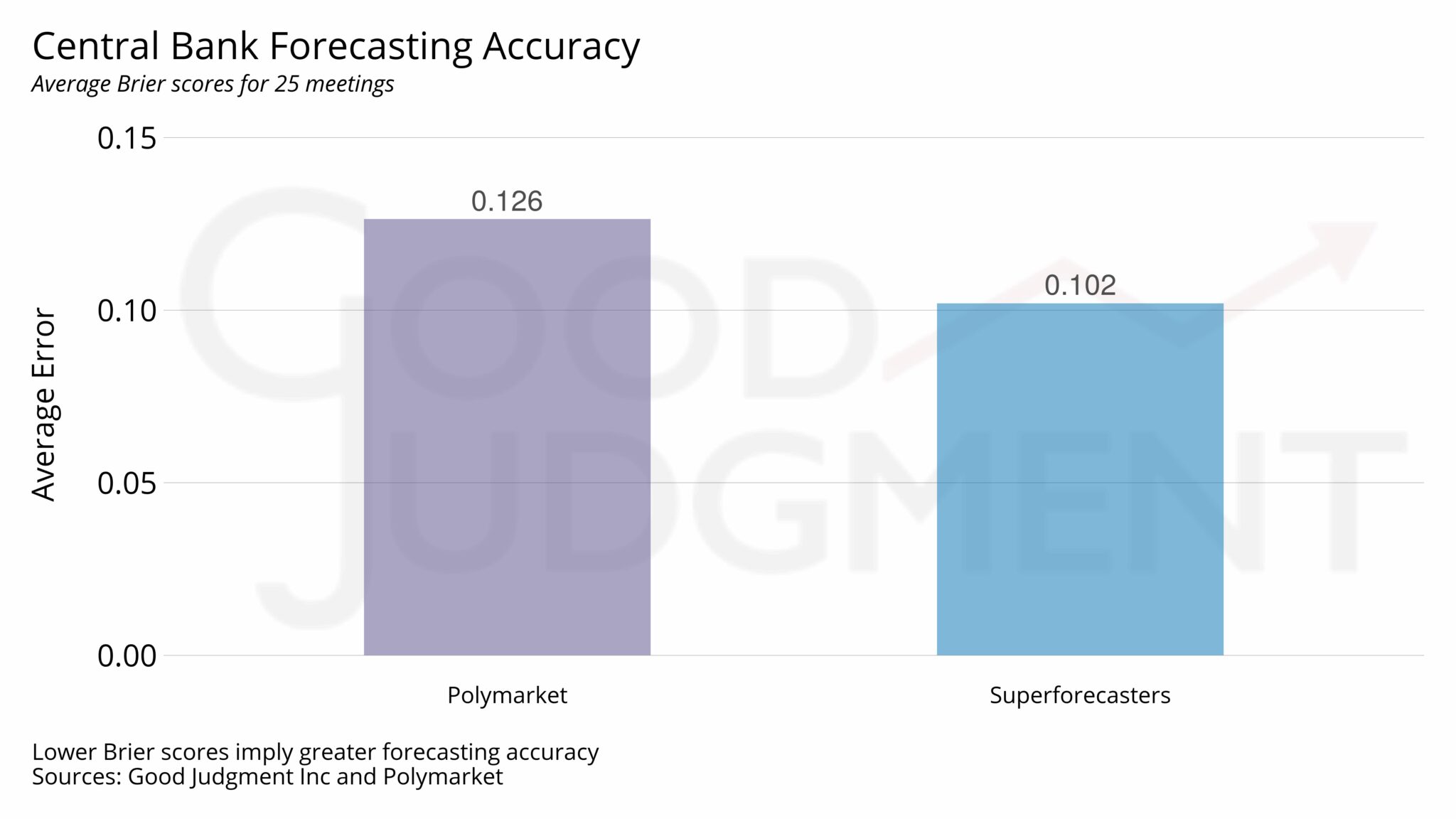

For each meeting, we aligned forecasts on three mutually exclusive outcomes—raise, hold, or cut—and evaluated probabilistic accuracy using the Brier score, the standard scoring rule for such forecasts. Lower scores indicate better performance, yielding a clean, apples-to-apples basis for objective comparison across platforms.

We used two complementary approaches, both pointing in the same direction. First, across all 1,756 daily forecasts, Superforecasters achieved lower (i.e., better) scores on 76 percent of days, with an average daily score of 0.135 compared to 0.159 for Polymarket. In other words, the prediction market’s performance was about 18 percent worse. Second, to account for unequal forecast horizons across meetings, we averaged daily scores within each meeting and then averaged those scores across the 25 meetings. On this basis, Superforecasters achieved an average score of 0.102, compared to 0.126 for Polymarket, making Polymarket roughly 24 percent worse.

This pattern is consistent with prior evidence. Superforecasters have a documented[2] history of strong performance in central bank forecasting, including comparisons against futures markets and other financial benchmarks, with coverage in The New York Times[3] and the Financial Times[4]. Taken together, the evidence shows that when forecasting systems are evaluated head-to-head on the same questions using standard accuracy metrics, the Superforecasters’ aggregate forecast performs better in this domain than prediction markets, undercutting claims of universal predictive supremacy.

* Chris Karvetski, PhD, is the Senior Data and Decision Scientist at Good Judgment Inc

[1] Polymarket coverage was not uniform across all central bank meetings. For example, forecasts were available for meetings in March 2024 and June 2024, but not for the 30 April/1 May meeting. Our analysis includes all meetings and all forecast days for which both platforms provided data, without selectively excluding any overlapping observations.

[2] See Good Judgment Inc, “Superforecasters Beat Futures Markets for a Third Year in a Row,” 12 December 2025.

[3] See Peter Coy: “A Better Forecast of Interest Rates,” New York Times, 21 June 2023 (may require subscription).

[4] “Looking at the data since January [2025], it is clear that the superforecasters continue to beat the market.” Joel Suss, “Monetary Policy Radar: ‘Superforecasters’ tend to beat the market,” Financial Times, October 2025 (requires subscription to FT’s Monetary Policy Radar).

Keep up with the latest Superforecasts with a FutureFirst subscription.

It’s been a challenging year. Public imagination has been captured by prediction markets and AI alike as potential oracles for, well, everything. And yet, here we are at Good Judgment Inc, not just standing but setting records.

It’s been a challenging year. Public imagination has been captured by prediction markets and AI alike as potential oracles for, well, everything. And yet, here we are at Good Judgment Inc, not just standing but setting records.