Handicapping the odds: What gamblers can learn from Superforecasters

Successful gamblers, like good forecasters, need to be able to translate hunches into numeric probabilities. For most people, however, this skill is not innate. It requires cultivation and practice.

In Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction, a best-selling book co-authored with Dan Gardner, Phil Tetlock writes: “Nuance matters. The more degrees of uncertainty you can distinguish, the better a forecaster you are likely to be. As in poker, you have an advantage if you are better than your competitors at separating 60/40 bets from 40/60—or 55/45 from 45/55.”

Good Judgment’s professional Superforecasters excel at this, but thinking in probabilities doesn’t come naturally to the majority of human beings. Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, who studied decision making under risk, found that most people tend to overweight low probabilities (e.g., the odds of winning a lottery) and underweight other outcomes that were probable but not certain. In other words, people on average evaluate probabilities incorrectly even when making critical decisions.

If you’ve participated in any Good Judgment training, you’ll know that the first step in estimating correct probabilities is to identify the base rate—the underlying likelihood of an event. This is also the step that the majority of decision makers tend to ignore. Base rate neglect is one of the most common cognitive biases we see in training programs and workshops, and it generally leads to poor investing, betting, and forecasting outcomes.

For those new to the concept, consider this classic example: “Steve is very shy and withdrawn, invariably helpful, but with little interest in people or the social world. A meek and tidy soul, he has a need for order and structure and a passion for detail.”

Is Steve more likely to be a librarian or a farmer? A librarian or a salesman?

While the description, offered in Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow, may be that of a stereotypical librarian, Steve is in fact 20 times more likely to be a farmer—and 83 times more likely to be a salesman—than a librarian. There are simply a lot more farmers and sales persons in the United States than male librarians.

Base rate neglect is the mind’s irrational tendency to disregard the underlying odds. Failure to account for the base rate could lead, for example, to the belief that participating in commercial forms of gambling is a good way of making money. Likewise, failure to factor in the house edge could lead to poor betting decisions.

Fortunately, the mind’s tendency to overlook the base rate can be corrected with training and practice.

Recognition of bias and noise, and techniques to mitigate their detrimental effects, should be at the heart of any training on better decision making. In Good Judgment workshops, we have consistently observed tangible improvements in the quality of forecasting as a result of debiasing interventions.

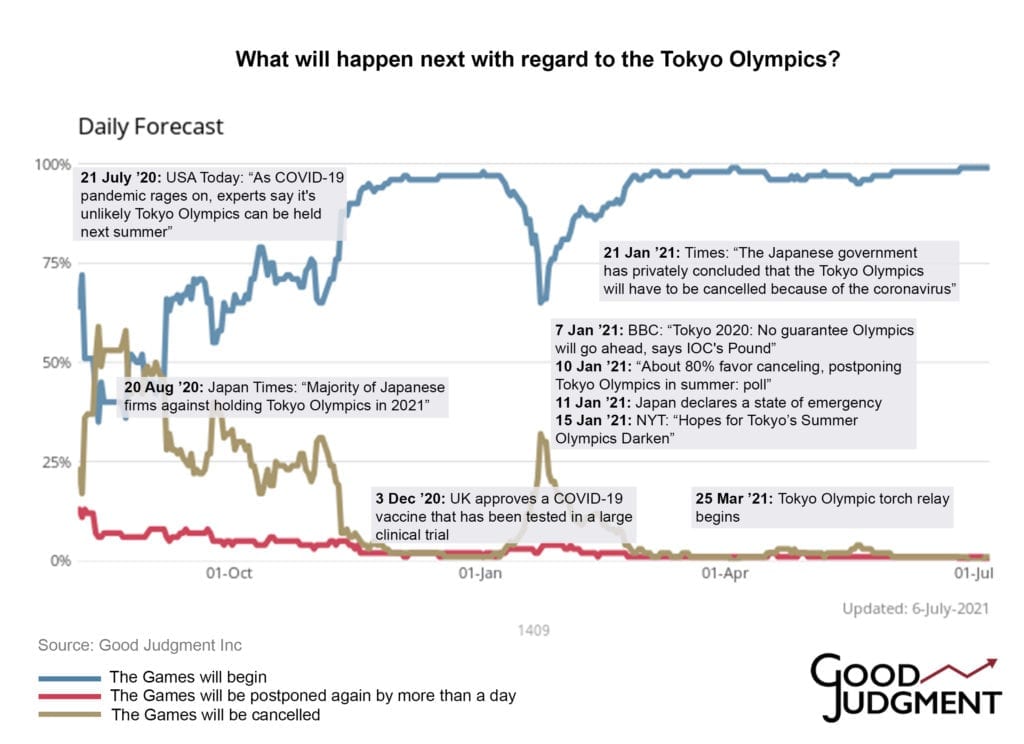

The other essential component is practice. On Good Judgment Inc’s public platform, GJ Open, anyone can try their hand at forecasting—from predicting the next NBA winner to estimating the future price of a bitcoin. Unsurprisingly, those forecasters who use base rates and forecast on the platform regularly tend to have better results.

To stay on top, gamblers, like successful forecasters and professional Superforecasters, need to actively seek out the base rate and mitigate other cognitive biases that interfere with their judgment. While “Thinking in Bets,” as professional gambler Annie Duke puts it in her best-seller, does not come easy to most people, better decision making—in forecasting, investing, and gambling alike—is a skill that can be learned. With an awareness of cognitive biases, debiasing techniques, and regular practice, anyone can acquire the mental discipline to handicap the odds more effectively.

* This article originally appeared in Luckbox Magazine and is shared with their permission.