Question Clustering: Ensuring relevance and rigor in business and geopolitical forecasting

Forecasting is an essential part of business. Companies use historical data and economic trends to make informed estimates of future sales, profits, and losses. Amazon and Google rely on predictive algorithms to highlight specific products or search results for their customers. Shopkeepers arrange their display windows based on their predictions of demand. Some of the forecasting is narrow and company-specific. The more challenging part has to do with broader questions, such as the overall market outlook.

Consider this question: What will market conditions be like after the pandemic?

This question is of great relevance to any business decision-maker, but it’s so broad that it could be approached from many different angles, using multiple definitions. “Market conditions,” for instance, involves multiple factors, from industry-specific trends to interest rates, from consumer spending to supply chains. How do we intend to measure this? What time frame are we looking at?

Much more tractable is a narrower question—”On 31 January 2022, what will be the average US tariff rate on imports from China?” But in checking all the boxes to craft a rigorous question, narrow topics may lose their relevance to decision-makers trying to determine the prospects for their business down the line. This is the rigor-relevance trade-off.

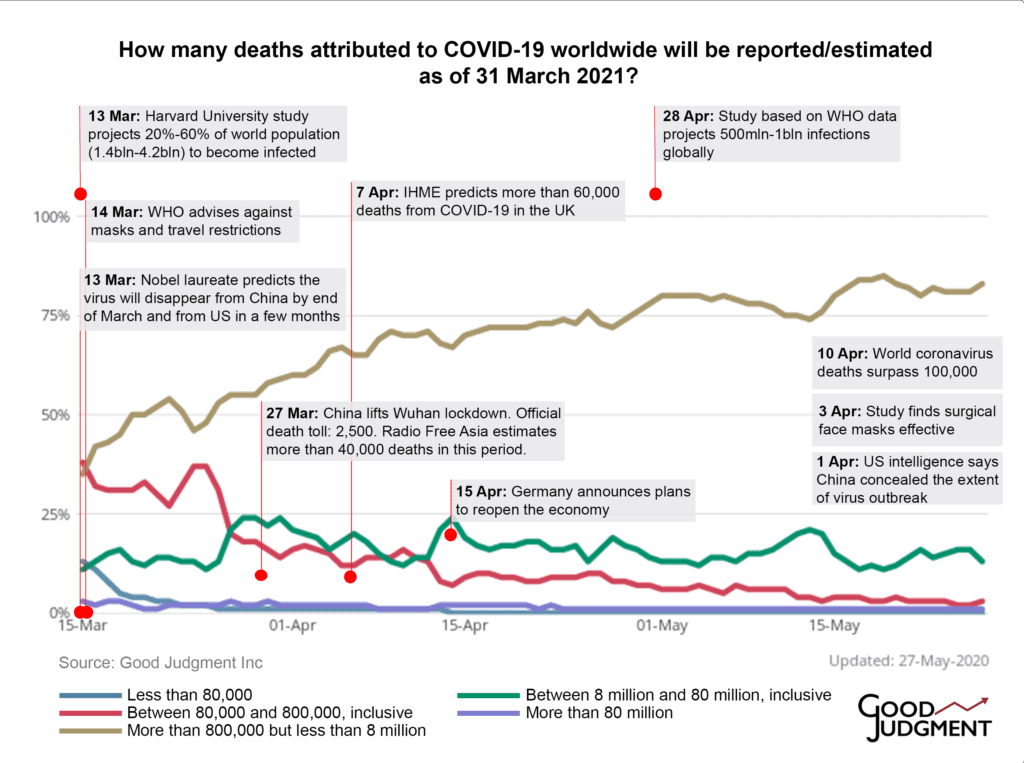

To tackle the relevant strategic questions that decision-makers ask with the rigor that accurate forecasting requires, Good Judgment crafts sets of questions about discrete events that, in combination, shed light on a broader topic. Good Judgment calls this technique question clusters. Good clusters will examine the strategic question from multiple perspectives—political, economic, financial, security, and informational. These days, a public health perspective is also usually worthwhile. Aggregating the probabilities that the Superforecasters assign to such specific questions generates a comprehensive forecast about the strategic question, as well as early warnings about the deeper geopolitical or business trends underway.

The Good Judgment team developed this method in a research study sponsored and validated by the US Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity from 2011-2015, where the Superforecasters outperformed the collective forecasts of intelligence analysts in the US government by 30%. Since then, the Superforecasters have refined and expanded their approach to evaluate emerging consumer trends, inform product development, and understand the factors driving commodity markets. A similar framework was detailed in a recent Foreign Affairs cover article by Professor Philip Tetlock and Dr Peter Scoblic.

As an example, a question cluster on a critical topic that clients have asked Good Judgment to develop includes political, military, social, and economic forecasts on emerging trends regarding Taiwan:

-

- Will Taiwan accuse the People’s Republic of China (PRC) of flying a military aircraft over the territory of the main island of Taiwan without permission before 31 December 2021?

- Will the PRC or Taiwan accuse the others’ military or civilian forces of firing upon its own military or civilian forces before 1 January 2022?

- Before 1 January 2022, will US legislation explicitly authorizing the president to use the armed forces to defend Taiwan from a military attack from the PRC become law?

- Will Taiwan (Chinese Taipei) send any athletes to compete in the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing?

- Will the Council of the EU adopt a decision authorizing the Commission to open negotiations with Taiwan on an investment agreement?

- Will the World Health Organization reinstate Taiwan’s observer status before 1 January 2022?

As another example, in forecasting the technological landscape, the Superforecasters estimate the emerging trends in electric car sales, hydrogen-fueled vehicles, the growth of Starlink services, and social media regulation, among others.

Independently, these forecasts are crucial for some companies and investors and informative for the discerning public. Taken together, they point to trends that are shaping the future of the geopolitical and business world.

The same technique can be applied to Amazon. The traditional approach of security analysts is to build a fixed model that predicts valuation based on dividends, cash flow, and other objective metrics. A question cluster approach can uncover critical subjective variables and quantify them, such as the risk of a regulatory crackdown or shifts in labor relations, to make the analyst’s model more robust.

“In business, good forecasting can be the difference between prosperity and bankruptcy,” says co-founder of Good Judgment, Professor Philip Tetlock. Successful businesses rely on forecasting to make better decisions. Using clusters of interrelated questions is one way to ensure those forecasts are both rigorous and relevant.

* This article originally appeared in Luckbox Magazine and is shared with their permission.