Superforecasters vs FT Readers: Results of an Informal Contest in the Financial Times

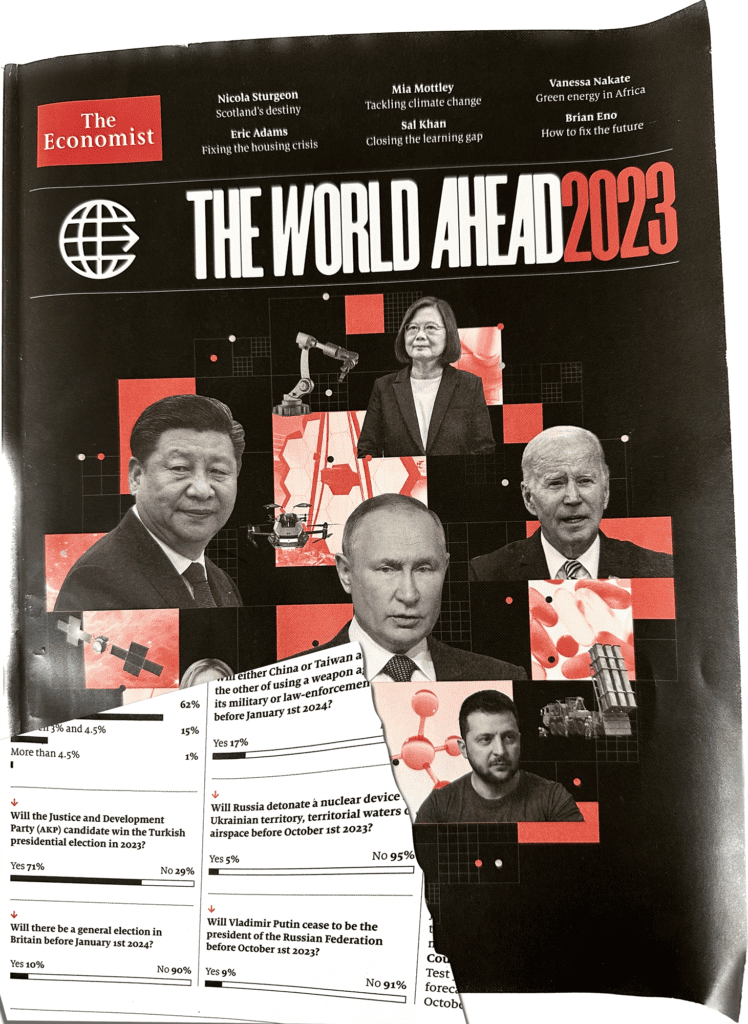

In early 2023, the Financial Times launched an informal contest that pitted the predictive prowess of the FT’s readership against that of Good Judgment’s Superforecasters. The contest involved forecasting key developments in the year ahead, ranging from geopolitical events to economic indicators to heat waves to sport. The results? Illuminating.

“To help illustrate what makes a superforecaster worthy of the name, the FT asked both readers and Good Judgment superforecasters to make predictions on ten questions early this year, spanning from GDP growth rates to viewership of the Fifa women’s world cup final,” Joanna S Kao and Eade Hemingway explain in their article.

A total of 95 Superforecasters made forecasts on the questions, while the reader poll had about 8,500 respondents.

The Results

Nine of the ten questions have now been scored. On a scale where 0.5 equals guessing and 1 equals perfect prediction, Superforecasters scored an average of 0.91 over nine questions, significantly outperforming FT readers who scored 0.73.

In this informal contest, the Superforecasters continued to work on the questions throughout the year, while the reader poll closed early. Based on everyone’s initial forecasts as of 2 February 2023, however, the Superforecasters outperformed the general crowd on eight out of nine questions.

Key to Forecasting Success

Key to the Superforecasters’ success, as the article notes, is their methodology. They focus on gathering comprehensive information, minimizing biases, and reducing the influence of irrelevant factors that only create noise. This methodological rigor stems from the foundational work of Philip Tetlock, a pioneer in the study of expert predictions and co-founder of Good Judgment Inc.

Read the full article in the FT for a fascinating glimpse into the realm of Superforecasting.

To benefit from Superforecasters’ insights on dozens of top-of-mind questions with probabilities that are updated daily, learn more about our forecast monitoring service, FutureFirst.

Ready to Elevate Your Forecasting Game in 2024? Embrace the Future with Our Exclusive End-of-Year Offer!

Join Our January 2024 Public Workshop – Unleash the Power of Accurate Forecasts!

➡️ What to Expect in the Superforecasting Workshop?

- Advanced Techniques: Dive into the latest forecasting methodologies.

- Expert Insights: Learn directly from top forecasters and researchers.

- Interactive Sessions: Engage in hands-on exercises for practical learning.

📈 Special Limited-Time Offer:

Claim your 20% discount on the January Public Workshop (16 & 18 January 2024). Use code GJ20XMS at registration. Hurry, offer valid while seats last!