$1 Trillion into AI, and It Still Can’t Ask the Right Questions

Superforecaster Ryan Adler on getting frontier LLM models to write solid forecasting questions.

Anyone hoping that artificial intelligence’s dominance of the headlines might wane in 2025 has been very disappointed. With over $1 trillion in announced investment, and December still to go, AI is permeating every aspect of society at an impressive pace. Perhaps most startling for many is the prospect that advances in these technologies will come for our jobs. While this fear is nothing new, it’s certainly accelerating.

As someone who, among other things, writes forecasting questions for a living, I’m not indifferent to the prospect of an AI model making my knowledge, skills, and abilities obsolete. That said, I undertook a recent exercise to evaluate the current state of the threat. Pleasantly enough, I found that frontier AI systems have a very long way to go.

What Frontier Models Get Wrong about Forecasting Questions

My colleague Chris Karvetski created a detailed prompt we used to ask ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude, and Grok to draft solid forecasting questions related to Russia’s war in Ukraine. This task requires at least a modicum of qualitative assessment, unlike simpler questions about, say, asset prices or interest rates. If that’s what you want, FRED already does most of the work. But war is different. It’s complicated; political and historical fictions abound; and the current Russian government is nothing if not creative on paper. Clear and salient forecasting questions are an absolute must for this and many other topics.

Here are a few quick observations:

- ChatGPT had an affinity for UN action, which should raise a red flag (no pun intended) for anyone familiar with the UN Security Council structure. Russian veto effectively prohibits any action that isn’t blessed by the Kremlin.

- Gemini seemed to presuppose perfect knowledge: that casualties down to the man and locations down to the kilometer were readily available data. They aren’t. Surplusage is also an issue, and its attempts to define controlling sources created potentially fatal inconsistencies.

- Claude tried to cover US and EU sanctions. On its face, it might look like a good framing. However, it tried to set a threshold (50%) without providing any notion of how the current spectrum of sanctions and restrictive measures would be quantified. Without clear metrics, that’s a complete nonstarter.

- Grok shared some of Gemini’s overconfidence in information availability and often framed questions that could only be resolved long after the fighting had concluded. That’s hardly useful for policymakers.

For those who have seen 1776, you may recall the scene where Thomas Jefferson first shares his draft declaration of independence. There’s a pause, then just about everybody in Independence Hall starts clamoring with questions. If the LLM-generated questions above were presented to Superforecasters, I suspect a similar scene of questions and clarification demands. Great forecasters know that the quality of a forecast, as well as the information derived from it, depends on every element of a question being as clear as possible. Otherwise, you may end up with a probability that means next to nothing.

Will one or more of these model lines get better? Certainly. Will a domain-specific program give us a run for our money before Halley’s Comet makes its return? Probably. But if Lewis and Clark’s path to the Pacific Ocean were an analogy for AI’s journey to writing iron-clad forecasting questions, today’s frontier models have just made it to Kansas City.

* Ryan Adler is a Superforecaster, GJ managing director, and leader of Good Judgment’s question team

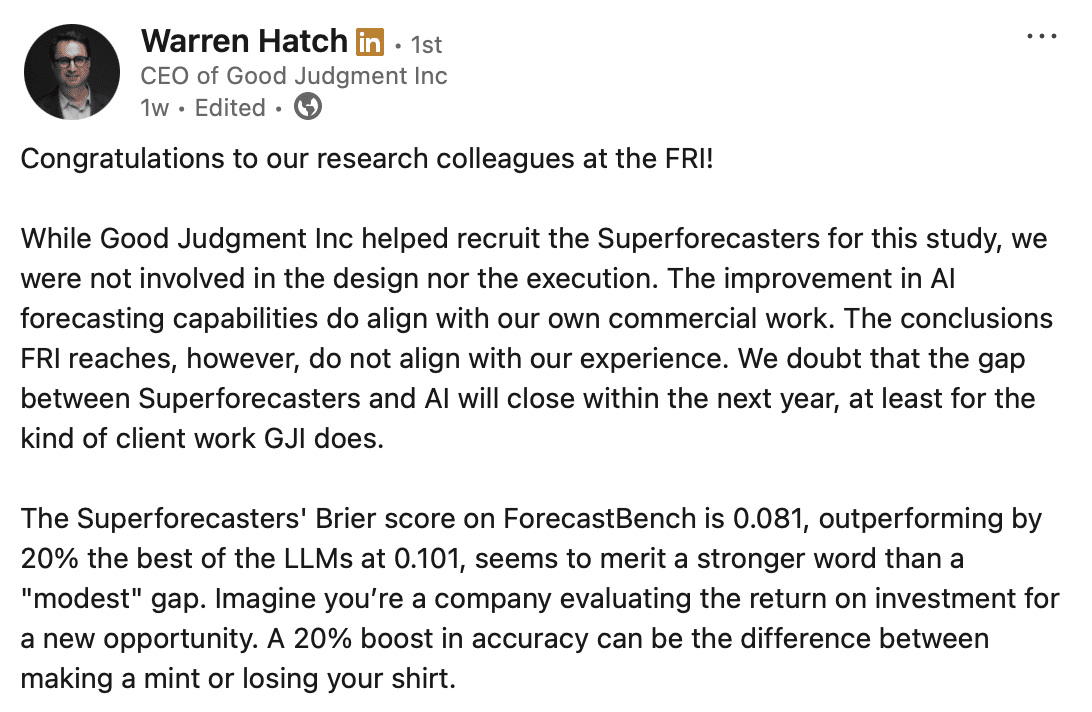

In October 2025, our colleagues at the Forecasting Research Institute released new ForecastBench

In October 2025, our colleagues at the Forecasting Research Institute released new ForecastBench