Superforecasting® Explained in Podcasts and Videos

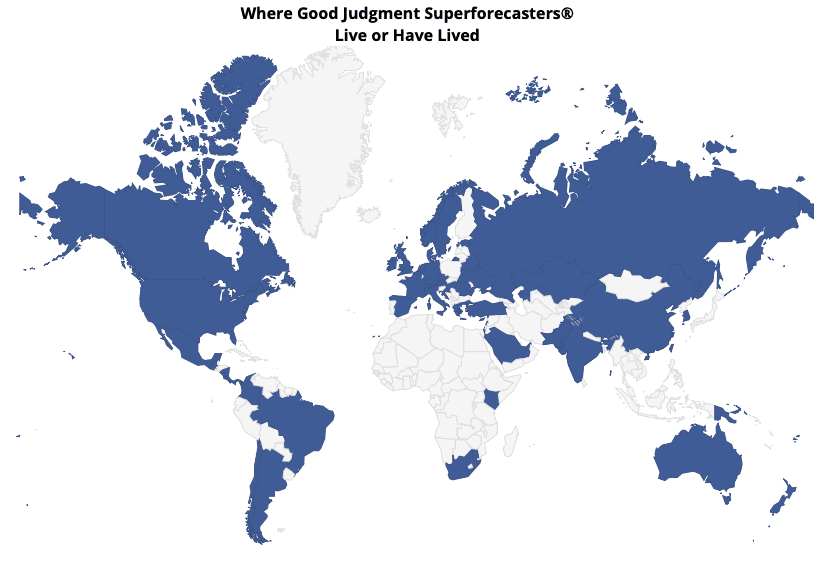

Superforecasting is a disciplined approach to forecasting that uses probabilistic thinking, continuous updating, and rigorous calibration to make well-informed judgments about future events. This approach is based on decades of research spearheaded by Dr. Philip Tetlock into what traits and tools make some people remarkably good at forecasting while others, including many experts, fall short. Since IARPA’s massive forecasting tournament of 2011-2015, Superforecasting has been proven to outperform traditional forecasting methods in many areas, including finance and policy decision-making (e.g., see our forecasting report on the early trajectory of Covid-19). Below, we’ve curated our favourite podcasts and videos that showcase the principles and real-world applications of Superforecasting.

Top 5 Podcasts and Videos

1. BBC Reel: Can You Learn to Predict the Future? (8:21)

This short video from BBC Reel introduces the concept of Superforecasting in an engaging and visual way. It explores the techniques that make accurate forecasting possible and discusses how anyone can improve their forecasting skills.

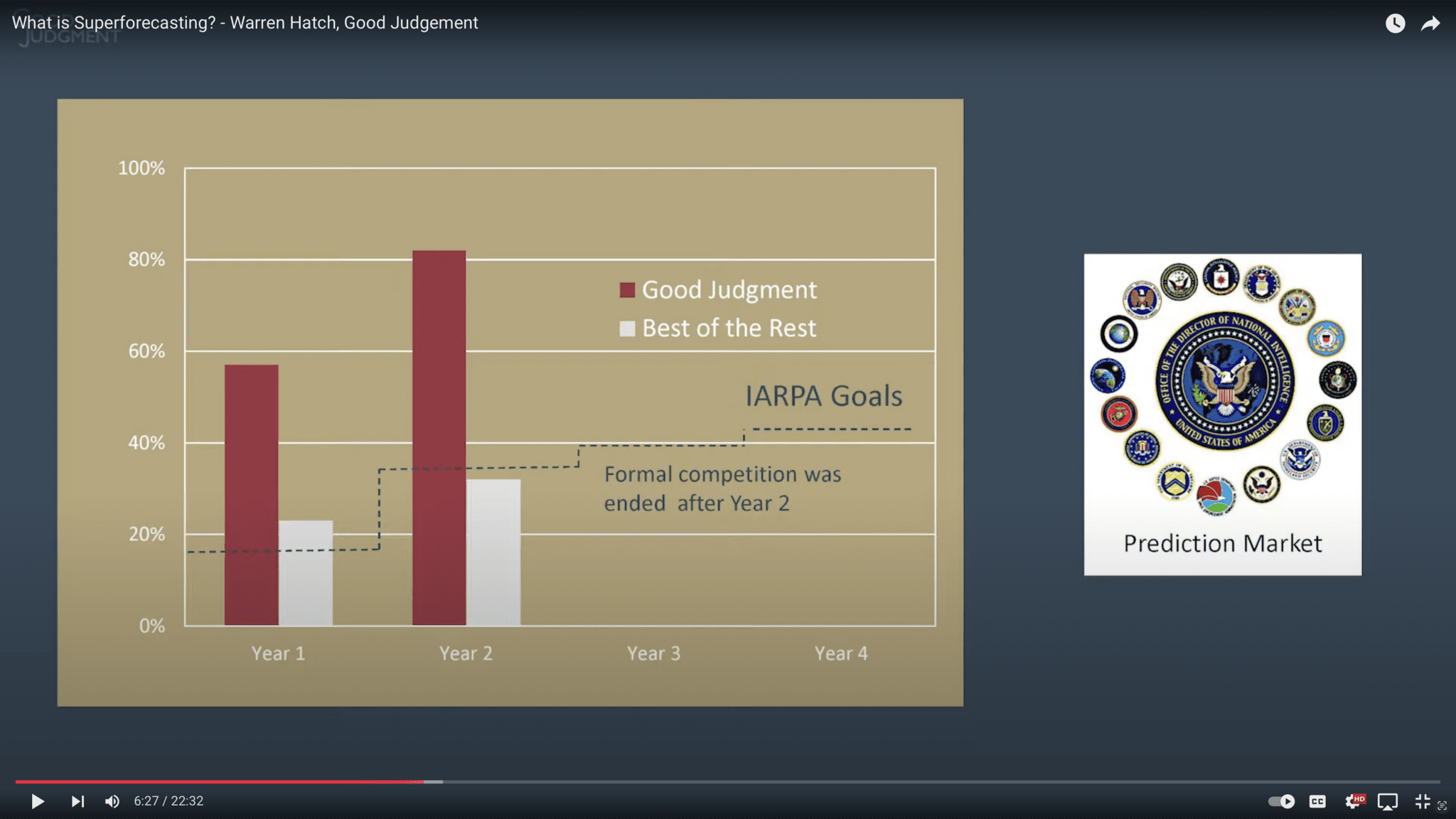

2. Quid Explore: Superforecasting with Dr. Warren Hatch (22:32)

In this detailed conversation, Dr. Warren Hatch, Superforecaster and CEO of Good Judgment Inc, explains the science behind Superforecasting. He discusses the traits of successful forecasters and shares practical tips for applying these skills in professional and personal decision-making.

3. More or Less: Superforecasting the Coronavirus (08:57)

Tim Harford talks to Terry Murray, GJ co-founder and project manager for the original Good Judgment Project (GJP), about how GJ Superforecasters tackled the uncertainties of the Covid-19 pandemic. This episode highlights how their methods and tools can be applied to making sense of real-world crises.

4. Talking Politics: David Spiegelhalter on Superforecasting (48:55)

Tim Harford talks to Terry Murray, GJ co-founder and project manager for the original Good Judgment Project (GJP), about how GJ Superforecasters tackled the uncertainties of the Covid-19 pandemic. This episode highlights how their methods and tools can be applied to making sense of real-world crises.

5. MarketWatch: Can an Ice Storm Predict the Next Meme Stocks? (25:38)

This podcast explores the intersection of forecasting and finance, showcasing how Superforecasting can shed light on trends in the stock market. In this episode, Dr. Hatch defines “prediction” vs “forecast,” describes the innate characteristics that make some people better at forecasting high-stakes world and financial events, and explains how anybody, whether they possess those innate characteristics or not, can get better at forecasting with practice.

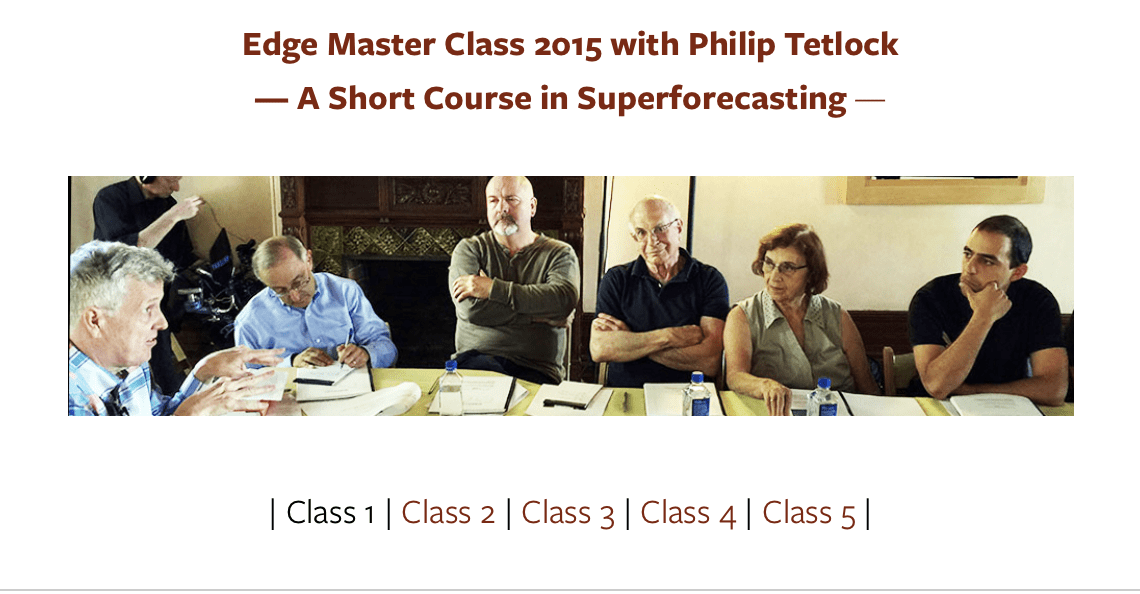

Take a Deeper Dive: Edge Master Class on Superforecasting

For those seeking a more in-depth exploration of Superforecasting, consider the Edge Master Class on Superforecasting led by Dr. Philip Tetlock. This short course covers the foundational principles and techniques of Superforecasting and features discussions with renowned experts (including Dr. Daniel Kahneman, the Nobel laureate in economics and author of Thinking, Fast and Slow; Dr. Barbara Mellers, a leading researcher in decision-making and another key figure behind the GJP; Dr. Robert Axelrod, a political scientist specializing in international security, formal models, and complex adaptive systems), as well as entrepreneurs and journalists.

From Theory to Practice

Whether you’re new to Superforecasting or want to deepen your understanding, these podcasts and videos are a great place to start! Ready to take the next step? Superforecasters’ methods and traits can be learned and cultivated. Start building your own forecasting skills with our training programs.

Nine years after the conclusion of the

Nine years after the conclusion of the