Superforecasters’ Toolbox: Beliefs as Hypotheses

Nine years after the conclusion of the IARPA forecasting tournament, one Good Judgment discovery remains the most consequential idea in today’s dynamic world of forecasting: the discovery of Superforecasters. The concept of Superforecasting has at its heart a simple but transformative idea: The best calibrated forecasters treat their beliefs not as sacrosanct truths, but as hypotheses to be tested.

Nine years after the conclusion of the IARPA forecasting tournament, one Good Judgment discovery remains the most consequential idea in today’s dynamic world of forecasting: the discovery of Superforecasters. The concept of Superforecasting has at its heart a simple but transformative idea: The best calibrated forecasters treat their beliefs not as sacrosanct truths, but as hypotheses to be tested.

Superforecasting emerged as a game-changer in the four-year, $20-million research tournament run by the US Office of the Director of National Intelligence to see whether crowd-sourced forecasting techniques could deliver more accurate forecasts than existing approaches. The answer was a resounding yes—and there was more. About 2% of the participants in the tournament were consistently better than others in calling correct outcomes early. What gave them the edge, the research team behind the Good Judgment Project (GJP) found, was not some supernatural ability to see the future but the way they approached forecasting questions. For example, they routinely engaged in what Tetlock calls in his seminal book on Superforecasting “the hard work of consulting other perspectives.”

Central to the practice of Superforecasters is a mindset that encourages a continual reassessment of assumptions in light of new evidence. It is an approach that prizes being actively open-minded, constantly challenging our own perspectives to improve decision-making and forecasting accuracy. As we continue to explore the tools Superforecasters use in their daily work at Good Judgment, we look at what treating beliefs as hypotheses means and how it can be done in practice.

Belief Formation

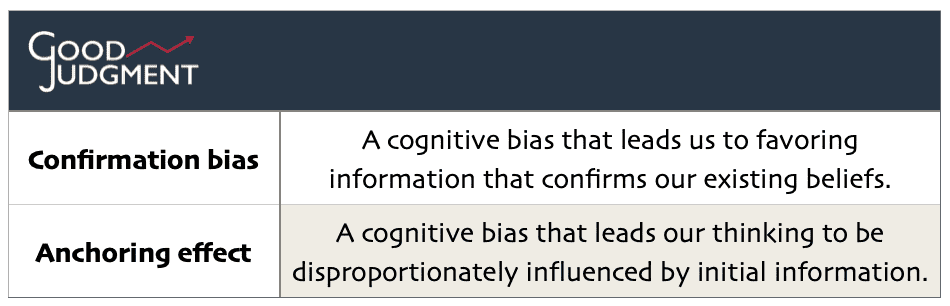

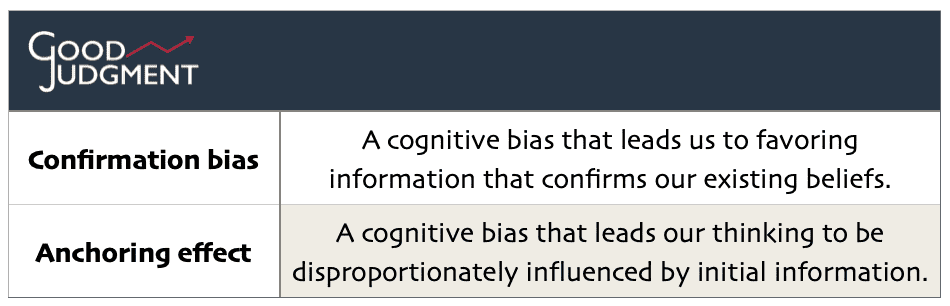

Beliefs are shaped by our experiences and generally reinforced by our desire for consistency. When we encounter new information, our cognitive processes work to integrate it with our existing knowledge and perspectives. Sometimes this leads to the modification of prior beliefs or the formation of new ones. More often, however, this process is susceptible to confirmation bias and the anchoring effect. (Both Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow and Noise, the latter co-authored with Olivier Sibony and Cass R. Sunstein, provide an accessible overview of how cognitive biases affect our thinking and belief formation.)

It is not surprising then that traditionally in forecasting, beliefs have been viewed as conclusions drawn from existing knowledge or expertise. These beliefs tended to be steadfast and were slow to change. Leaders and forecasters alike didn’t like being seen as flip-flops.

During the GJP, Superforecasters challenged this notion. In forecasting, where accuracy and adaptability are paramount, they demonstrated that the ability to change one’s mind brought superior results.

The Superforecaster’s Toolkit

What does this mean in practice? Treating beliefs as hypotheses means being actively open-minded. That in turn requires an awareness and mitigation of cognitive biases to ensure a more balanced and objective approach to evaluation of information.

- To begin with, Superforecasters constantly question themselves—and each other—whether their beliefs are grounded in evidence rather than assumption.

- As practitioners of Bayesian thinking, they update their probabilities based on new evidence.

- They also emphasize the importance of diverse information sources, ensuring a comprehensive perspective.

- They have the courage to listen to contrasting viewpoints and integrate them into their analysis.

This method demands rigorous evidence-based reasoning, but it is worth the effort, as it transforms forecasting from mere guesswork into a systematic evaluation of probabilities. It is this willingness to engage in the “hard work of consulting other perspectives” that has enabled the Superforecasters to beat the otherwise effective futures markets in foreseeing the US Fed’s policy changes.

Cultivating a Superforecaster’s Mindset

Adopting this mindset is not without challenges. Emotional attachments to long-held beliefs can impede objectivity, and the deluge of information available can be overwhelming. But a Superforecaster’s mindset can and should be cultivated wherever good calibration is the goal. Viewing beliefs as flexible hypotheses is a strategy that champions open-mindedness over rigidity, ensuring that our conclusions are always subject to revision and refinement. It allows for a more effective interaction with information, fostering a readiness to adapt when faced with new data.

It is the surest path to better decisions.

Good Judgment Inc offers public and private workshops to help your organization take your forecasting skills to the next level.

We also provide forecasting services via our FutureFirst™ dashboard.

Explore our subscription options ranging from the comprehensive service to select channels on questions that matter to your organization.